As the 12 December is Universal Health Coverage Day, it is worth remembering that on 10 October 2019, the world’s governments agreed a UN General Assembly resolution committing themselves to achieving Universal Health Coverage for all people across the life course. It was hard fought and the agenda it sets out is both comprehensive and ambitious. At its core, this Political Declaration recognises that health is an investment and necessary for fully realising our human potential. It also makes clear that health is a fundamental human right that is necessary for promoting and protecting the dignity and empowerment of all people.

As difficult as it was to get this agreement, implementing it is even harder. Universal Health Coverage means that everyone, everywhere can access the health and care services they need without suffering financial hardship. Putting this into practice means taking into account a shifting health landscape, as well as different national priorities, and having to contend with many, many vested interests within the health sector. It also means recognising that the status quo is not working for addressing the majority of the world’s health needs.

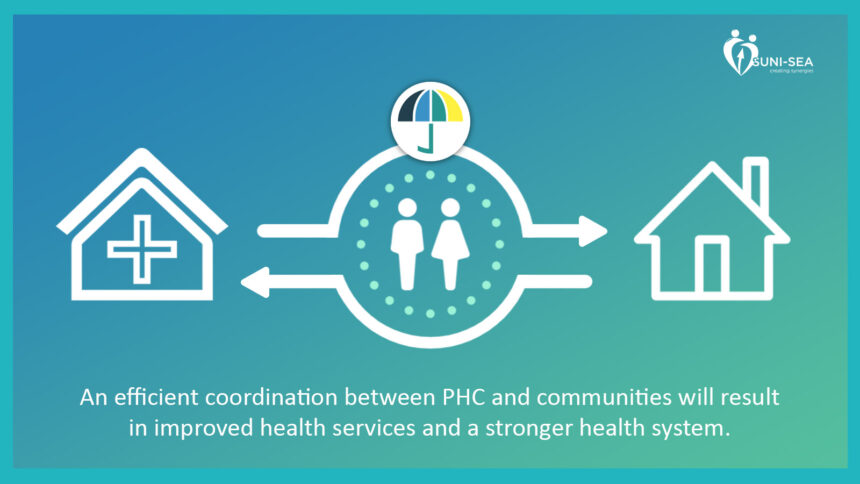

But not everything has to be contentious. Some things stand out in the Declaration as being foundational for achieving these aspirations. Primary health care, empowering people and communities, and community-based services are recognised as being the cornerstone of a sustainable system for universal health coverage.

Another important pillar of this agreement was the commitment to ensuring healthy lives and well-being for all throughout the life course. This follows from the important standards set out in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 3) that refers to both achieving better health and well-being “for all at all ages” and the crucial pledge to “leave no one behind”. This is important not just from the perspective of basic rights, but also because demographic realities demand it. Universal health coverage that does not respond to the health needs of older people is not universal.

Another important pillar of this agreement was the commitment to ensuring healthy lives and well-being for all throughout the life course. This follows from the important standards set out in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 3) that refers to both achieving better health and well-being “for all at all ages” and the crucial pledge to “leave no one behind”. This is important not just from the perspective of basic rights, but also because demographic realities demand it. Universal health coverage that does not respond to the health needs of older people is not universal.

By 2030, 1.4 billion people will be aged 60 or over, and the majority of the world’s older people currently live in low and middle-income countries. Taking a life course approach to universal health coverage is not an aspiration, it is a necessity. Nowhere is this truer than for the countries of South-East Asia. This region is undergoing a rapid demographic transition making it imperative that the health and care needs and rights of older people are at the forefront of governments’ concerns.

Meeting the health needs of ageing populations requires an approach to health that places the person at its centre. In this sense, healthy ageing is about enhancing the capacity of people to continue to do what matters most to them as they age. Putting this into practice has to incorporate the meaningful participation of older people in decision making about their own health and the design of people-centred health services. It also means placing greater emphasis on improving the collection and analysis of data, investing in assistive technologies, and putting into place long-term care and support.

Globally, the significance of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) has also come to the fore, accounting for up to 70% of deaths worldwide. NCDs include chronic conditions like cancers, cardiovascular disease, stroke, chronic respiratory diseases, diabetes, and mental health and neurological disorders among many others. One cannot achieve universal health coverage without taking into account the prevention and management of NCDs at all stages of the life course.

It is for this reason that the project “Scaling Up NCD Interventions in South-East Asia” (SUNI-SEA) was established. Taking place in Indonesia, Myanmar and Vietnam, 10 consortium members are collaborating on a four-year implementation research project to evaluate and validate scaling-up strategies of diabetes and hypertension prevention and management interventions.

Crucially, SUNI-SEA takes as its starting point that community involvement and strengthening primary healthcare interventions—including the linkages between health systems and the community—will have a greater impact on the ability of governments and people to both prevent and manage NCDs. It will also be more sustainable financially for the overall health system.

In Vietnam, the project is partnering with the Vietnam Association of the Elderly and is working through Intergenerational Self-Help Clubs to organise community-based health screening and health promotion for hypertension and diabetes risk factors. Representatives of local government, the local health service and community members have all commented how interventions of the research have been helpful.

In Vietnam, the project is partnering with the Vietnam Association of the Elderly and is working through Intergenerational Self-Help Clubs to organise community-based health screening and health promotion for hypertension and diabetes risk factors. Representatives of local government, the local health service and community members have all commented how interventions of the research have been helpful.

The research from the EU-funded project will be completed by June 2023. While it is too soon to tell what the final conclusions will be, the lessons learned will hopefully contribute to improving national government NCD scale-up plans and also to the review of the 2019 UN NCD Political Declaration that will be taking place in 2023 culminating in a further High-Level Meeting on NCDs in September 2023.

One thing is certain: the process of working with communities and the primary healthcare system is already reaping results in terms of reaching more people with awareness about NCD risks and prevention, as well as increasing access to NCDs screening services. On its own though, this is not enough; additional health care staff, medical equipment and essential medicines are very much needed. Achieving UHC needs more investment in community-based and primary health care level interventions. Hopefully the UN High-Level Meeting in September will result in a renewed effort to make improving the health and well-being of all people at all ages a reality.

Written by: Ken Bluestone, Head of Policy and Influencing for Age International